Last Saturday I spoke at NGV’s Symposium, Art and the Connected Future, one of the public talk programs that runs alongside their, understandably popular, Andy Warhol/Ai Weiwei exhibition. I was particularly chuffed to be invited because, given my currently dire financial situation, the last time I’d been in Melbourne I couldn’t afford the entry fee. This time not only was entry to this most excellent of shows (in both content and presentation) free for speakers and delegates, but I was also flown over, put up in a swanky hotel for the night and paid to talk – luxury! More seriously I was delighted to be part of what I imagined to be a fascinating dialogue around arts, technology and social change framed by the life and work of two of the world’s most prominent creative troublemakers. On that last point, I may have missed the mark somewhat. I’ve been in the creative digital world for twenty years now, over eight of those spent living in Australia. I hadn’t asked, but I imagine they invited me because of the work I’ve done with the-phone-book Limited, ANAT, the Australia Council for the Arts and my general technoevangelism. In retrospect I’m not sure they were expecting the techno-cynic and fully-immersed social change voice that I have unquestioningly become.

Amongst an inspiring lineup for the day (I storified the tweets for those interested in far more of the day’s excellent convo than I have given due attention to in this post), my panel session was “Technically Speaking: Art, Artists and Audiences” with Seb Chan (ACMI), Kathy Cleland (University of Sydney) and Ben Davis (an American arts critic, who had kicked us off with an excellent Keynote just before), and chaired by Simon Crerar (Buzzfeed). The questions we had been asked to consider were: How have artists been redefined by digital developments in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? How are artists using digital and social media to shape their art, and their artistic identity? What recent developments in the digital realm have impacted the art world and the ways we engage with art? How have digital advances extended the reach and power of art and artists? Why are museums and art galleries using new technologies? What impact does this have on audience experiences?

While I hope I brought some considered responses to these areas of thought, I couldn’t help but bring things back to the role of artists, institutions and technology gatekeepers in a contemporary society dominated by capitalism. With all the destruction capitalism (and its political bodyguard, neoliberalism) wreak on arts, culture and human existence, why are we still asking the same art/technology/audience questions which simply maintain a broken status quo?

To put this in context, in January Ai Weiwei pulled his exhibition in Denmark in protest to their asylum-seeker laws… so why was the NGV’s exhibition still going ahead? This country seems to pride itself on maintaining a reputation for some of the worst human rights abuses in the Western world. I’m certainly disgusted by our Government’s treatment of innocent humans asking for help… so why is Ai Weiwei OK with Australia’s asylum-seeker policies? (I have asked, but still don’t have an answer). After twenty years in this space I’m truly disappointed with where digital culture is going as a whole. Particularly with regards increased surveillance (bolstered by physical anti-protest laws nationally and the corporate sponsorship of law enforcers), proprietary and closed online platforms (where we are the product, not the customer), and ongoing battles against net neutrality. Perhaps I’m therefore not the best person to evangelise about how artists can help institutions gain better engagement with audiences through technology in quite the way I used to.

I’ve got to admit, twenty years ago I had high hopes for the future of our digital world. I believed the internet could finally gave us all a much-needed equal voice, that it would connect niche like-minded communities across vast geographic distances and empower users to meaningfully engage with anyone, anywhere, regardless of physical or economic capability. I’ve been pondering a full article reflecting on twenty years of my role in creative geekery and the trends (both good and bad) which I have watched emerge, but in summary: the doubts which had always lurked in the back of my naively optimistic mind have sadly come to fruition. Instead of the utopian digital democracy the internet could have become, we find ourselves addicted to algorithms that commodify our character and homogenise our humanness. Instead of enthusiastically embracing innovative business models and amplifying the increased voices of the many, our media monoliths have somehow managed to both profit behind paywalls and abuse our airwaves – simultaneously! The same tools which enabled us to participate in vital social movements like Arab Spring and Occupy are equally those which threaten the freedoms of whistleblowers. Indeed in at least one of Ai Weiwei’s documentaries in the exhibition, The Fake Case, he mentions that his very name is banned from Chinese internet. What sets us free can also destroy us.

But what does all this geeky social change talk have to do with artists? For me, everything. Over the last few years, as I have shifted my existence more fully into the activism world, I quickly noticed the similarities between processes. An artist has a concept, an idea they wish to communicate, and (most of the time) a clear idea of who they wish to communicate it with. They then need to find partners and resources to enable that idea to become real and present (be that in physical form or not). Then they have to create a buzz, awareness, marketing, to bring those audiences to the work, evaluate those engagements and reflect on what was revealed and what that means for future work. Then the cycle starts all over again with a new development of the same concept or a whole different tangent altogether.

Now go back to re-read that section but replace the word ‘artist’ with ‘activist’; ‘a concept, an idea’ with ‘a cause, an issue’ and ‘audiences’ with ‘supporters’. See? It’s the same process.

One of the roles of the arts is to hold a up mirror against society. What we see reflected back at us is often unpleasant, uncomfortable, unnerving… and necessarily so, especially in contemporary times. As Alison Croggan says in “On art as therapy” (Overland):

Sometimes art makes you anxious. That is part of its job. Sometimes its therapy exists in bringing to the surface our hidden traumas, our worst crimes, our darkest, most secret desires, and then forcing us to confront them. Making art is a process of examining our psychic unease in order to see it more clearly, inflaming rather than anesthetising our discomfort and pain. Art names our terrors as well as our joys. Sometimes, in order to make things better, art first has to make them worse.

This ‘unease’ is something that both Warhol and Weiwei do quite superbly, and for which they are much loved… by some. Sadly others disagree. The Australian’s 2014 article, “Sydney Biennale Shame Risks Funding says George Brandis” (published behind a paywall) gave us a glimpse of the dark times to come (a story we all know well). Artists boycott the Sydney Biennale because one of its key sponsors, Transfield Services (now called Broadspectrum, presumably to confuse us), make significant profits from maintaining the inhumanely-legal torture chamber known as Manus Island. Brandis spits his dummy, demanding that The Australia Council punish these -and future- sinners for biting the hand that feeds (despite the fact that increasingly it Does Not Feed!). Australia Council maintains its ‘arms length to the Government’ stance… and subsequently gets fined $104.7million… from budgets that largely affect the independent and small to medium arts sector… who are the ones most likely to create work that demonstrates our social unease and challenge the status quo. Sigh.

Still reeling from the ramifications of these OzCo cuts (and the newly proposed $8.5million cuts to arts funding in SA – for heaven’s sake, why can’t we be more like VIC?!), a couple of days ago we got a whole new kick in the gut: “Catalyst” (Brandis’ personal, non-transparent, slush fund for already-doing-quite-well-thank-you-very-much-but-sure-we’ll-take-a-few-hundred-thousand-more-because-we-can organisations, and one or two well-we-don’t-happen-to-be-your-friends-but-we-promise-not-to-be-naughty artists and orgs) is pork barrelling, using drip-fed grants announcements as photo opps for their election campaigning. [I read this news as I was about to board the flight back to Adelaide. I was horrified, disgusted, and so physically upset that I worried my visibly shaking body and laser-angry eyes wouldn’t be allowed on the plane. I even spent time exploring a delicious daydream of forcing some kind of legal action against them (imagine, the arts taking down these scumbags! bliss!)… but sadly that was not to be. I’d never heard of pork barrelling before. It may be immoral and unethical, but shamefully it turns out using public funds designated for the arts is neither illegal nor breaches electoral commission regulations. They’re good at that, this Government. If nothing else you do have to admire their astonishing capacity to make you physically ill while fully complying with the law… but then they do get to write those laws, sooooo… yeah. You see why artists need to be activists?! But I digress…]

As I wrote recently, the arts are increasingly becoming commodified and we, as the creative sector, need to both be aware of this fact and be ready to act on it – whether we are indies, SMEs or the ‘I’m alright Jack’ larger, safer, arts organisations and institutions. The arts is an ecosystem and we are ALL at risk if ANY of us are at risk. Any self-determination we felt we had as a sector is being both subtly and overtly chipped away, through internal funding cuts and bully-tactics, and external proprietary platforms and the power they wield (which in itself perfectly mirrors our social condition as a whole, not just within the arts).

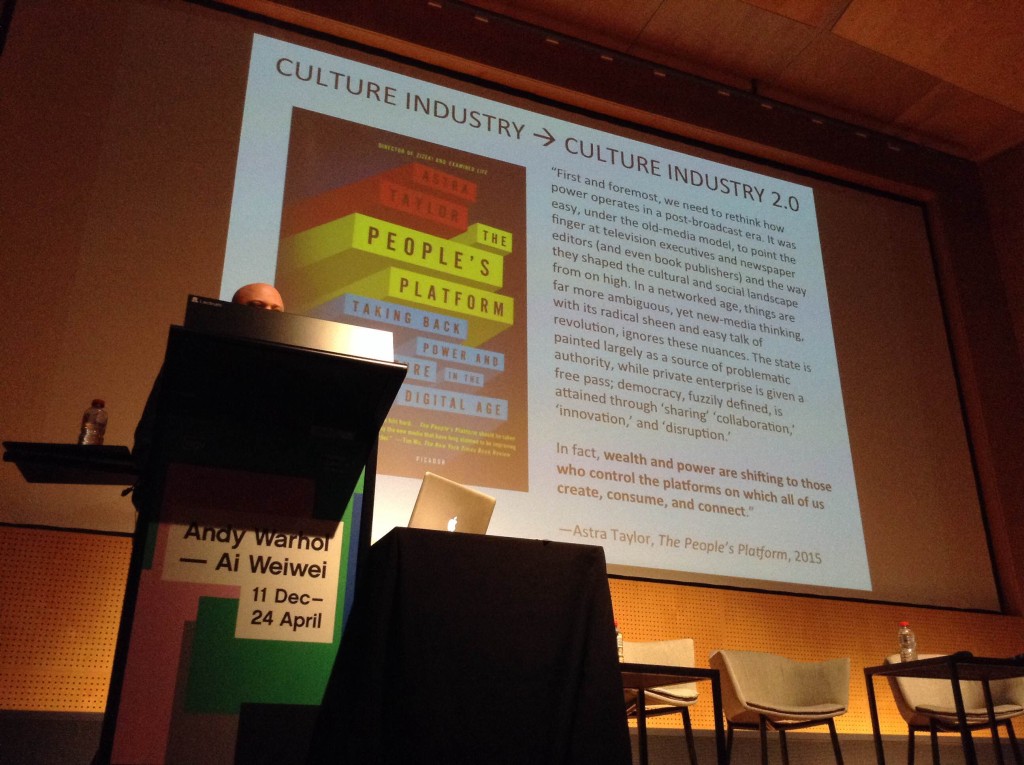

a slide from Ben Davis’ Keynote featuring a fabulous quote from “The People’s Platform” by Astra Taylor

Our NGV symposium chair, Simon Crerar, kickstarted the day by proudly sharing the recent viral success of Buzzfeed’s exploding watermelon on Facebook Live. Some online felt this astonishing feat foretold ‘the key to the future of TV‘; Simon, perhaps, felt it was the exciting future of digital arts. To me, not so much, but as we observe independent, otherness, voices struggle to gain attention or support amidst the myriad of homogenised, force-fed-by-algorithm tripe that our mainstream world has become… maybe I’m wrong.

As academic Hugh Davies mentioned in his talk on Ai Weiwei, frustrated by an all-encompassing police surveillance he established a live broadcast of his home and studio… which was shut down by police after 46hours (too much of a good thing, maybe?!). Hugh’s point – these days we may struggle more with a “fear of NOT being watched”, than the fear of “to be watched is to be an activist” (latterly referring to the German film, The Lives of Others“. I’m all for ownership of the creative experience by audiences, but these days I fear the author isn’t so much dead, it’s just getting a damned sight harder finding their signal through the noise. Personally I prefer the cheeky subversion of Paolo Cirio’s Street Ghosts and the Surveillance Camera Players over complicit acceptance of the pervasive panopticon of technological giants and the masters with whom they share our most private of correspondence.

Ben Davis’ illuminating keynote dropped a fascinating statistic into this with his comparison of high arts and games engagement. Where current tracking technologies have calculated that a museum or gallery-goer may spend up to 30seconds on a single artwork, an immersive gamer is spending 72hours a session, fully engaged and hyper-stimulated. This begs the question: where is the sublime gaze lingering longest, and what does that say about our current appreciation of the arts and culture? (… at least the kinds of art one may find in your average gallery or museum). Bring on more Slow Art Days, and alternative spaces outside the hamster wheel where we can pause, reflect, take stock before continuing with a calmer, more focused mind (like maybe hammocktime, heh). We’ll need them when the global shortage of colouring pencils hits hard.

Perhaps we as artists and our symbiotic relationship with museums and galleries is part of the problem. As Ben pointed out, John Berger’s Ways of Seeing mooted that in the future museums will be replaced by the equivalent of mood boards… enter Pinterest. Tom Uglow (Google’s Creative Lab) talked of “Art Project“, ‘The world’s art at your fingertips’ and the joy of accessing astonishingly high-resolution scans of artworks from the world’s foremost collections. Yes the technology and access potential is remarkable… but does that access negate our need to experience these works in the flesh, for ourselves, with all of the user-journey that comes from the sights and smells of the physical contexts outside the doors of the Uffizi or the Musée d’Orsay? Are we risking archiving our creative collections as artefacts instead of living, breathing, contemporary influences?

I can’t help but fear that our habitual colonisation – the capture, collection and selective release of paintings or sculptures depicting the natural environment (like some kind of Royal Society pioneer with his samples, carefully harnessing the magic of reality and preserving it in formaldehyde, or with a pin, in a glass box) – has sucked the very life out of them. The very act of taking these images or shapes from their natural context (owning it, co-opting it into our everyday, a form of scientific-cyborg assimilation) removes their otherness, their magic, their rarity. Knowing that they are always there, on demand, ticks some kind of psychological box negating our desire to even remember that one day we might want to experience them – perhaps even in person.

Don’t get me wrong, I recently visited the “Santos Museum of Economic Botany” in Adelaide (note the corporate branding) and it was a rare pleasure to view their permanent collections. But consider how little access children have to the natural world in its raw context these days – we have zoos, parks, botanic gardens, but are these not just factory farms? Colonies of artefacts, preserved for posterity while we destroy every last remaining natural habitat on the planet in the search for profits? We all grieved when ISIS destroyed the Palmyra and countless precous artefacts. But are we all simply heading toward a dark age where we will no longer require the original because we have a high-resolution scan, modelled in virtual reality for us to investigate through a mouseclick or 3D Print for ourselves at home? What if our scientists, artists and institutions are just as much to blame, or at very least partly accountable, as our capitalist enemies for bringing forward the end of the world as we know it (albeit with diametrically opposed intentions)? What a terrifying concept. And if this is true, what can we do about it, as individuals and collectively? And what power, if any, do I, we, as independent artists hold in turning things around? Pointing a finger alone risks biting the ubiquitous non-feeding hand, and even that strikes a chord of fear (this post’s critical backlash concerns me, and I’m not even answerable to anyone other than myself).

And what of artists collaborating with these technological giants? Media artists are always inventing, innovating new technological solutions as they problem solve in the process of their making. What if those inventions may inadvertently cause harm if controlled by the wrong hands. I asked Tom a ‘somewhat hyperbolic question’ (his words, justifiably), “Knowing you’re essentially working for ‘evil corp‘ (despite their claims to the contrary), what barriers, if any do you place on the development of new works which could end up in the wrong hands? Are your Creative Labs no-holds-barred, or do you ever stop to consider the potential risks? Would you cut down a project in its prime if it were, say, to become the equivalent of the next atom bomb?” (His answer was that the tech is usually already Google’s IP which artists are accessing, but that yes some of those thoughts are present).

Ben’s detailed, contextual talk revealed that the concept of ‘independent artist’ is a relatively new construct. Most major artists of yore operated in studio environments with apprentices, making work to order in a manner more akin to contemporary design than what we understand of contemporary DIY makers/producers. These emerging independent artist roles coincidentally revealed themselves around the time of the Industrial Revolution; the beginnings of capitalism begets the ‘artist labourer’. So in fact the relationship between independent artist and social change warrior has never really changed since its inception (I feel somehow empowered by that!).

As an artist your projects change you, or at least, they can… if you let them. I know my lifestyle choice has changed not just my outlook on every aspect of life and my place within it, but my entire physiology (I wasn’t expecting that!). I think about my own responsibilities a great deal, so naturally left the event pondering the responsibilities of institutions like NGV, what their role in society might be amongst the multitude of threats we face today. I wondered if hosting an exhibition of major international arts activists had changed the NGV in any meaningful ways. I’ve left them with that question and genuinely hope to receive an answer… to that, and a few more they won’t be expecting.

As seems to be my habit these days, I’m going to close yet another TL;DR post with some thoughts that risk biting the hand that feeds. I realise after the debate around the changing role of Adelaide Fringe and its backlash (both public and, more painfully, in certain deafening silences) that I’m going to earn myself a reputation of uneasy critical reflection. But if we don’t ask these questions, reflect these mirrors, then we are accepting of these status quo’s. I do not comply with the trajectory our society is on, and surely where is this civil disobedience more appropriate than in a discussion about Warhol and Weiwei? I am grateful to NGV for a really inspiring day and for being treated quite fabulously – spoiled, in fact. But these questions remain, and I am left needing to ask them, for better or worse, not just to NGV (although some below are specific reflections from the day) but to all our cultural institutions, worldwide. Even if you’re not hosting a socially engaged arts practice within your walls, shouldn’t every artistic institution (and indeed every institution) step up – speak out against injustices, reflect on adaptations to their own status quo, fight back against this never-ending, destructive, capitalist onslaught?

I started this post mentioning the exhibition ticket price ($26 – yes I really am that poor right now) being outside my reach, and certainly I wouldn’t have been able to afford to fly over and pay the symposium’s $70. If that was a barrier to me, what would that mean for others? Had they made efforts to seek more diversity in their audiences by removing those economic barriers other than simply a concession rate (still expensive at $22.50)? And although there was a good gender balance in the speakers, we were all gleamingly white. The auditorium itself was far from packed, and also largely white. Had efforts been made to invite broader diversity in cultural and economic background? If so, what could they have done to improve things, and if not… why not?

Should any conference held in times where we’re faced with undeniable ecological disaster, provide water in small bottles destined for landfill, not from a jug and a few glasses? Were leftovers from the kitchens that provided our deliciously decadent lunch offered to the many homeless people shivering on the cold street outside, with cardboard signs that began “I don’t want to be here…” What else can we do – as organisations and individuals – that can redirect our significant privilege to those who struggle to even exist? Sure we don’t get huge salaries in the arts, but we still have more than others. While our governments refuse to step up, hiding behind ‘austerity measures’ and immoral legal systems, it’s up to us to consider these painful truths.

And then there are the even bigger questions, imbalances from so long ago they can seem too distant to even fathom. The National Museum of Australia in Canberra has been hosting ‘Encounters’, a temporary exhibition of Indigenous artefacts on loan from the vaults of the British Museum. Shouldn’t they be returned for good, not just to Australia, but to their living custodians?

And why, when independent artists are so definitively under threat, are these institutions still asking us how we can help them to maintain their engagement with audiences, when so few of them have stepped up and spoken out against these cuts? Is it seriously the role of independent artists, digital or otherwise, to preserve our cultural institutions, when perhaps it is us ourselves who are most in need of contemporary artworld preservation?

Perhaps some of these questions can be brought forward to tonight’s Art & Activism debate – if so I would love to hear their responses. I note sadly that no independent artists are speaking, something that was questioned by our audience and is all too common at these discussions. But then when you invite indies, treat them fabulously and then watch in horror as they speak with a criticism that burns, perhaps I’m doing both myself and others a disservice for speaking my mind. Time will tell…