I was invited to be a Keynote Speaker for the MINAmobile2016 conference in Melbourne over Skype (I’m in North Wales for family reasons right now) because of my experiences running an arts org which specialised in mobile and emerging media between 2000-2008. That work – as all work in our strange and beautiful creative sector does – has informed who I am as a person and explains why and how I do what I do. It’s a long read, includes bits I had to cut from the talk for time and yet misses so very much out. Give yourself a good 45minutes… but since it covers eight years of the phone-book Limited and five years of reallybigroadtrip and I’m generally TL;DR, I think that’s not too bad at all! Huge thanks especially to Dean Keep who invited me to talk and has been a wonderful colleague and friend since participating in an early Masterclass we ran in Sydney in 2004/5.

Acknowledgement to Country

Before I start my talk I would like to acknowledge that sitting in that audience over in Melbourne, you (and by electric extension, we) are meeting on the lands of the Wurundjeri Peoples of the Kulin nation, and I therefore pay my respects to their Elders, past present and future. I extend that respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Peoples as the traditional custodians of this land we now call Australia. This always was, and always will be, Aboriginal Land.

Likewise many of you will know about the Sioux nation, the water protectors, currently battling all odds at Standing Rock in North Dakota. I would like to think that we all stand in solidarity with all First Nations Peoples who continue to fight for the rights of humankind to clean air, clean water and a healthy and sustainable natural habitat for all living things. These are trying times for our planet and humanity as a whole. I call upon my ancestors from the North Welsh mountains, from where I speak to you now, to stand with them, with all of us, in the battles to come.

Introduction to the-phone-book

the-phone-book Limited was a creative media agency based mostly from our lounge room in Manchester, UK. Bouncing from that base to communities all over the world, we spent eight years (2000-2008) encouraging people to be creative with the technology they carried in their pockets. Our art was essentially the creation of spaces and challenges which provoke others into creative responses.

Given the iPhone – which, allegedly, ‘launched the mobile content industry’ – didn’t get around to doing so until 2007, this was quite an ambition. Fortunately a combination of curiosity and blind ignorance meant we didn’t know what we didn’t know, which makes it harder to realise what you’re getting into.

As geek-minded artists, we were fascinated by the limitations of the mobile technology – the hardware and software, and the gateways and internet protocols which stitched them all together. On top of that, mobility provides an entirely new creative limitation; you have no idea what the technical capacity of your audience’s devices might be, nor where they might happen to be while they are engaging with you. Does their device have a speaker or a headphone socket? Are they on the bus, at work, in the pub or at home? “Limit the artist and you lend them wings” was a mantra we often repeated.

In 2000 the world wide web, still in its early days of rhizomatically expanding into a more mainstream home user experience, rightly demanded to be free to end users. As creative producers we foresaw that things would not be so ethical for its mobile counterpart. So why not harness that potential commercial mobile marketplace before it had even been born, and turn it into a source of revenue for the creative industries?

I mentioned blind ignorance… well, in reality what we wanted – what I wanted – was to change the face of international business and help artists make and sell their own work, however that might materialise. Of course the mobile content market wasn’t there yet, and wouldn’t be for many years to come, but somehow we knew it was on its way.

Artists are often early adopters, so… wouldn’t it be cool if by the time the rest of the world caught up, there was already a network of makers with portfolios of content made specifically for mobile devices, and their peripatetic users, ready and waiting to be enjoyed and shared? Yeah, we thought so too.

Over our eight years, we commissioned and published collections and ran education programs and calls to arms, all designed to raise awareness and knowledge about these emerging technologies and the human interconnectedness they promised. Together, we generated stories, images, videos, performances, ringtones, logos, operating system themes, wikis, and basically any other type of creative experience that it eventually became possible to deliver through and around a mobile device.

But first, there was the green screen. And only the green screen.

How it came about

A few years before, I had switched focus from Theatre prop making and stage management to the creative digital world. I’d completed an MA in Interactive Multimedia Production – the first of its type in the UK, located within the school of Computing and Maths since, as usual, no one saw technology as anything other than a commercial domain to be exploited.

One night my then-partner (in life and creativity), Ben Jones, had been digging around in the back end of the server I’d set up after uni. He was a performance maker by training, morphing into a Cinematographer with a specialism in stop motion animation, but as anyone here knows, the geek virus is an infectious little bugger.

“I’ve discovered our server supports WML!” he said, excitedly. “What’s WML?” I asked. “Well, that’s what I thought. So I’ve done some digging and discovered it’s ‘wireless markup language’, the language of WAP, ‘wireless application protocol’, which is basically mobile internet”.

“There’s a mobile internet?!”

And so began yet another of our many creative collaboration explorations.

It went something like this…

F: What does it do?

B: Not much, it’s made up in decks of cards. Each card holds approximately 150 words of text, or black and white, bitmapped, images. The general consensus is “WAP is crap”, but , yknow, LoFi is cool so why couldn’t WAP be cool too?

F: OK, so what can WE do with it?

B: Well, we could take copyfree content, like Shakespeare’s sonnets or something, and republish them.

F: Or… we could commission writers to make new works specifically for it?

B: Could we?

… Having worked briefly at North West Arts Board (NWAB, our regional funding agency) I’d started to get my head around arts funding and had been looking for something to try out. This seemed ideal – new platforms, new audiences, a new creative challenge for writers… what’s not to love?!…

F: Sure! *schemer cogs turning* there’s something in this…

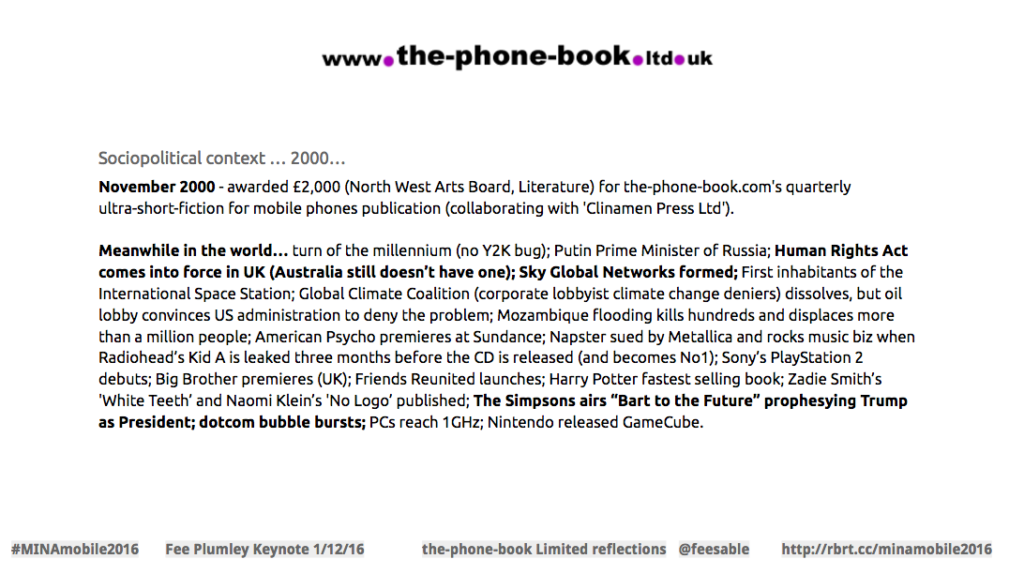

Despite being avid readers and lovers of Literature, neither Ben or myself felt suitably equipped to run a writing commission. Fortunately a friend, Ben Stebbing, was in the process of setting up a publishing house, Clinamen Press, so we took him the idea and asked if he’d like to come on board as our Editor. He loved it. We had a team.

That week we drafted a one pager of the idea to take to NWAB, asking only for £2000 to spend on commissioning writers. The Literature Officer loved it, despite having no idea what we were talking about technologically. The Media Arts Officer was less convinced, “No one is going to read short stories on their mobile phone!” she said. (And yes, she still hates me telling this story… I won’t name names – and she was far from being the only naysayer – but she has eaten her words many times since then!).

We called the project the-phone-book.com, because it quite literally turned your phone into a book. We wanted short stories, not poetry, and we would pay commercial rates for the works we published – better rates than The Observer! NWAB wanted the collection to be focused on North West of England writers, which is pretty hard to do when you’re calling openly online for a digital commission, but we promised to try.

We called the project the-phone-book.com, because it quite literally turned your phone into a book. We wanted short stories, not poetry, and we would pay commercial rates for the works we published – better rates than The Observer! NWAB wanted the collection to be focused on North West of England writers, which is pretty hard to do when you’re calling openly online for a digital commission, but we promised to try.

This being an entirely new space we knew we had to educate not just our audiences, but our creators. The call for works consisted of home-printed flyers shared around local North West writer communities, bookshops, libraries, art galleries, bulletin boards, internet cafe’s, theatres, comedy clubs, film sets, etc, and press releases sent to local media. A bit later we shouted online via elists and forums, particularly those centering around ‘flash fiction’ (back then generally 1500-5000 word stories) and the more experimental arts spaces who would ‘get it’.

We didn’t have any money other than the commissioning budget and couldn’t even afford to buy one of the ‘swanky’ new WAP-enabled mobile handsets to test on. There were ‘wap emulators’ online, but as you will all know, testing has to be done in its native environment. Again, ‘limit the artist and you lend them wings’ came into play… Back in those days phone shops were walls of fully functioning gadgets on security cords. Ben and I would go in, one of us would pretend to want to purchase, and the other would quickly type in the url of the test page and make notes on what worked or didn’t. It was at that point that we realised that a long url incorporating several hyphens and backslashes was a completely stupid idea for keypad devices…! By the time every shop in the city had cottoned on to our sneaky behaviour, we’d saved enough to buy one of our own, the Matrix-inspired Nokia 7110.

And so it began…

What we commissioned/produced/taught; why, and how

the-phone-book.com

the-phone-book commissioned ultra short stories of 150 words or less, 50 words or less and 150 characters or less. For each quarterly edition we published a WAP site and a web site, the latter including a set of spoken word recordings of every story. We paid professional rates and charged our readers nothing (who on earth would pay for content on a platform they didn’t even know existed?)

For over a year and a half every edition was hand-coded in both wml and html, and audio recordings were made in our lounge in Manchester on basic DIY studio equipment. I read the female stories and our friend Dave Williams, (who unlike me actually was a trained performer) read the male stories. We encoded them as realaudio files and published them on the website only (WAP couldn’t handle audio).

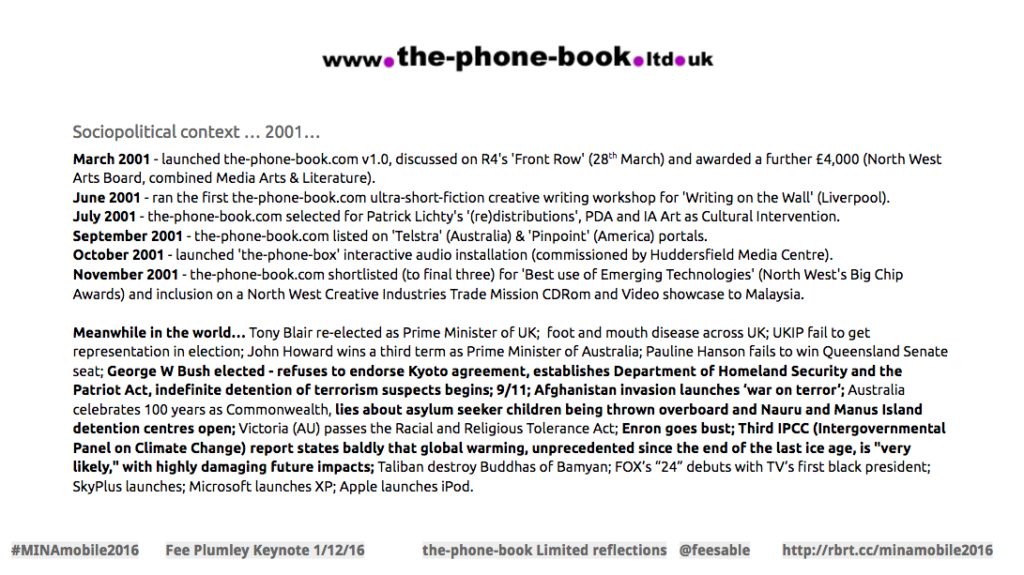

By March 1st 2001 our first edition was ready to go live, featuring 34 stories, selected from a submission pool of around 300, costing the princely sum of £750. That first release was nerve-wracking, but exciting: upload final two index files… clear cache… reload desktop browser… check mobile version, yes it’s up and working. Send out announcement mailshots. And then we sat back and waited nervously to hear the responses from our authors…

They loved it. And what was even more exciting was that BBC Radio4’s Front Row (the UK’s best cultural program on the radio) had somehow managed to get wind of it, giving it a National review that (our) money couldn’t buy. There had been a text message poetry competition run by The Guardian around the same time and guest poet Simon Armitage had been brought in to discuss it. However he seemed more curious about our short story challenge for WAP than a text message poetry competition run by a major newspaper. With that and a few articles in local media, by the time we went back to the funders to see what they thought, we were the talk of the town!

Most of our visitors were regular readers and also submitted; it was the perfect community. We spent a lot of time on this, crafting our communications to make everyone feel like a welcome individual, even when dealing with mass mailshots or promo. We printed a small distribution run of 3,000 postcards choosing three favourite works for the front, with an invitation to write one of your own to send back to us on the reverse. The marketing aimed to invite experienced, published authors but also promote the idea that anyone could have a go.

We offered our authors their own email addresses, firstnamelastname@the-phone-book.com, as an email forward – it made me so proud seeing how many people took us up on that offer (and cunning promotional tool)! Over the first year we found ourselves receiving high ratings on various ‘Top Paying Writer’s Markets’ and being discussed in online writing communities lists. People totally understood the creative challenge; saw the benchmark of work already published; enjoyed conversing with us about the production side of it all; loved seeing their work within such a novel format; got a kick out of hearing their work being read out by strangers with different accents; and of course enjoyed being remunerated well for their efforts.

Our second funding meeting confirmed an extra £4,000 toward the project. Over the first year (four editions) we published 220 stories on a budget of £6000, which by then included a fraction toward the costs of servers, internet access, etc, but still nothing toward the time our team spent promoting the call, editing the submissions, coding the sites, recording the stories, managing the writers and generally bringing it all to life. We loved every second of it. Despite these tiny budgets by the end of the first year we were getting around 4,000 visitors a month to the sites, and had about 1,000 people on our email list.

Payments to selected writers were made by cheque, then by mid-way through our second year, micropayment gateways started to become more trusted. PayPal made our lives a thousand times easier – certainly mine, since I was the one hand-writing all the cheques. A newly-selected writer from USA emailed me once, saying he was so delighted to have become ‘a professional writer’ for the first time that he was planning on framing the cheque. I had to gently remind him that if he didn’t cash the cheque he technically wouldn’t be able to call himself a professional writer, and maybe he should photocopy the cheque and frame that instead. Some found our showcase so novel it made them newsworthy in their own hometowns, which brought in even more work for them. We were doing good. For everyone.

It was a busy year, with ultra-short-writing workshops lead by our Editor and one of the authors from the collection at a local writing festival. And on the other side of the Pennines, Huddersfield Media Centre took such a fancy to the idea that they commissioned us to turn it into an installation for their hi-tech innovation hub’s foyer to entertain people waiting for their meeting to happen. the-phone-box went on to be exhibited at the Liverpool Biennale (2002) and has sadly been languishing in a friend’s attic ever since – let me know if you’d like it in your foyer some time!

Arts Council England’s national office got wind of us, too, with an officer from the Literature Department’s National Touring Program reaching out for a meeting. Turns out they wanted us to apply to them to expand the concept. So our little £6k project became a major £65k project, keeping us going for three years with bigger and bigger editions and releasing 1000 spoken word CDs in a 3disc box set, and 4000 anthologies of the first year’s collection in limited edition sets with handmade covers. They were, of course, pocket-sized. Later a collaboration with Futuresonic (then a sound arts festival) lead to the creation of a DJ Scratch Battle tool; 10” red and 12” black vinyls, using words and phrases from the collection mixed with beats and battle breaks.

By the end of that project, December 2003, we had a collection of 935 stories written by 330 writers from 24 countries, and were receiving approximately 3000 submissions a quarter with 1500 unique visits per day.

the-phone-book Limited

As the-phone-book.com found its own rhythm, Ben Jones and I started getting curious about what else mobile devices could do. What had started as a project partnership between the three of us became a Limited company made of Ben Jones and myself with various collaborators brought in as outsourced freelancers. With the rapid development of mobile devices looming and talk of the future of convergence (with few knowing what it even vaguely meant), it was time for business planning…

Around the same time we were watching the explosion of the ringtones and operator logos market. Curious as to how artists could get in on this commercial action, we wanted to dig around there too. Art+ringtones = artones (we’re very literal)!

Mobile phones by then (2002) were capable of wap, as we’d learned. That included limited text and bitmapped images. In moaning about the corporate world’s lack of interest (e.g. a British Airways WAP site that showed a logo for three seconds then flicked to a text page that said “Please visit our website at…”) Ben spotted something interesting. Being the moving image guy, he wanted to know more; if a timer command could be used once, it could be used multiple times, right? So essentially he created a ‘flickbook animation generator’. And so the-sketch-book was born.

Suddenly, we had a portfolio: the-phone-book.com, artones.net and the-sketch-book.com. We were a company.

artones.net

Handset owners personalised their devices with snap-on covers, operator logos, ringtones, caller group graphics and screensavers, each making their own statement about their owner. We had observed that the vast majority of distributed content internationally was pure push-marketing; take your pick of ‘Nike’ style graphics to replace your operator logo, or a range of the latest ‘S Club’ pop songs to choose as your ringtone.

The bulk of copyright on those items was owned by one central company who leased the rights of reproduction to smaller agencies, offering a lucrative income for the distributors at an average cost of £5.00 each item. The result of that system is that the content is generalised and unoriginal – a paradox to the aim of ‘personalisation’, we felt.

We offered an alternative to the range of content available to users, bringing the artistic and commercial worlds together with artones.net. Funded through a North West Arts Board ‘action research project’, we commissioned Nick Crowe (Manchester), Lucy Kimbell (London) and Thomson & Craighead (London) to create new works of ultra-small-art for distribution to mobile phone handsets. These works were published to a web and wap site and our premium rate sms gateway. The works were sold to UK GSM handsets for approximately £2.50 each.

The idea was that the creative value of the artist’s work would then be defined by its literal market value; as the logos and ringtones are sold, the artist would gain 50% of profits taken for the sale. All information concerning how many sales of which items would be published quarterly on the web and wap sites so both artists and fans could monitor their progress. We’d launch with a first set of ringtones and logos and see how it went from there.

The project launched on September 12th 2002 for the Liverpool Biennial Independents Programme with White Diamond before going on to feature within the Thomson & Craighead’s dot-store.com launch at London’s ICA from September 18th.

In reality, we barely made any sales at all (but we gave away a lot both for education purposes and promotion). Turns out a tiny arts organisation on zero income can’t really compete with the budgets of major copyright holders – who knew?! But we had provided a generous initial commission fee to the artists, and they were more interested in the creative challenge than changing the face of international business.

The project concept for us as commissioners was threefold:

- Mimic the marketing strategies of content distributors working with mobile technologies

- Question the artistic response to such a brief (e.g. would the commercial aspect of the project affect the creative design process? If an item sold, would the artist make more or less items in that style?)

- Question the consumers’ response to alternative content (e.g. would consumers who spend approximately a quarter of a million pounds a week on popular culture items consider buying artistic content? What items would sell? Would ‘limited edition’ items be more or less popular?)

The creative/technical brief was remarkably simple, asking that our artists create:

- Ringtones – limited to single channel midi at 44Ghz for approximately 8 seconds (.rtttl).

- Logo’s – limited to 72 x 14 pixels, black & white (.nol).

We provided software and instructions and were on-hand to answer any questions they might have during the process. We made no other demands and let them take the challenge wherever they chose.

What came back was stunning. Nick Crowe was inflamed by George Bush winning the American election the year before and more so with the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Bush had also banned all trade links, including the sale of software, with those, and other, countries which he defined as the ‘axis of evil’. Nick wanted to rebalance this bigotry, so created his ringtones out of their National Anthems.

Thomson and Craighead were interested in reclaiming brand identity space by spoofing corporate logos, and creating morse code ringtones, a set of family tones which would work in harmony if all family member’s phones rang at the same time and, as an homage to John Cage, the silent tone.

Lucy, who was fascinated with economics and had been exploring the corporate valuation of creativity and life through her project, the LIX Index, (and was a fan of Naomi Klein’s recent publication “No Logo”), stated exactly that: Logo, No Logo.

We gave them empty ringtones and logo spaces to fill. They came back with political statements. Whouldathunk?!

the-sketch-book

As with all technologies, we knew WAP, rtttl and operator logos would eventually become obsolete as the long-awaited 3G devices started being rolled out, with their promise of receiving and sending streamed audio and video. We already had experience with animation, film production, music, webstreaming and curation elsewhere online, so it was obvious to work with these new technologies as they emerged on mobile. As always, anything we learned we turned into creative commissions and education programs for others, be they writers, painters, filmmakers, musicians or programmers.

Following the same ideals as the-phone-book.com, the-sketch-book became a physical and server-based education program exploring ultra-short-moving image media for wireless and traditional internet. It all started with the wap animation, re-appropriating the “on-timer” command and turning lo-res images into flick books. Ben created a code generator, the beauty of which was in the ‘dramatic reveal’ – in order to publish the work online you had to copy and paste (and optionally, edit) the code. It was sneaky, we were normalising the abnormal, making code friendly and accessible. It was lovely.

As the hardware improved, handsets became capable of viewing colour photographs instead of just bitmapped images, then, eventually 3gp video. Our programs expanded accordingly. Once we’d educated a few groups via festivals and community projects we started running ‘made for and by mobile’ short video calls and showcases, expanding our offerings as we toured the entire portfolio of education programs and digital content exhibitions around the world.

Our education programs were commended for their pedagogy, for which I must entirely credit Ben. He is gifted with a generous, accessible manner which was essential for teaching such unknown unknowns. We centralised the experience down to known knowns first – what can you make for YOUR device? Handsets were so diverse, especially back then, it was hard to know where to start, or why to bother, until you’d made a personal connection.

While massively open and flexible in everything else, we had certain rules in our classrooms. These two were my favourites:

- The participant’s hand is always on the mouse – if you take control and show by doing it yourself you’re essentially sprinkling magic dust over it all. Digital learning especially has to be lead by the user or else it’s not their experience and is too abstract to be believable.

- Never answer a question – sounds mean, but given the multiple ways content could be created/encoded for multiple handsets/gateways, as soon as you provide an answer you determine a ‘one size fits all’ rule. That limitation is absurd for most digital content/thinking, especially mobile, especially back then, and it shuts down thinking. So no matter what the question, and no matter what answers we knew to be out there, we’d always respond with “I don’t know, let’s have a go and see what happens”. That way the questioner finds THEIR answer for THEIR context, thereby learning how to ask/answer anything for themselves. It worked brilliantly. The only annoying times were when someone popping in who hadn’t picked up our intention would assume we didn’t know, or were being lazy, and would try to answer directly ‘on our behalf’. We’d have to take them outside and explain: either play the game, or shut up (said nicely, of course :P)

No matter whether we were running the ‘seven minute challenge drop-in’ or multi-day masterclasses, the findings (and therefore the teachings) were the same:

- There are no rules.

- Test on as many handsets & services as possible.

- Their solution might not be your solution.

- Consider the ‘quality to cost of carriage ratio’.

- Even the professionals use quicktime to encode.

The education program was taken to the Croatian Split Film Festival for their New Media Telekom Art Exhibition, the eCulture Fair in Holland, the European Media Arts Festival (EMAF) in Germany, and the Aichi Geidai Prefectural Art University in Japan (where we added i-mode and 3G / FOMA elements since they were years ahead of the Western world in mobile content creation) before exhibiting at the International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA2002) in Nagoya. Since we were also exhibiting the-phone-book.com collection there too we had a number of stories translated into Japanese for the event – culturally this was apparently somewhat unusual and we found local audiences to be smilingly grateful for our efforts.

Ours were physical education programs that incorporated technology as opposed to eLearning more specifically, although we did get involved with mLearning. In terms of eLearning generally (learning through the mechanisms of technology, without physical presence or even sometimes any live shared remote sessions) I found (both then and now) that the technology often gets in the way; digital literacy becomes a barrier to itself.

Business, too, gets in the way, as we found with the whole ‘WAP conspiracy’. On arriving in Japan the most common question to the limitation of our short story commission was “why?”. imode was the most commonly used Japanese mobile internet platform, provided by NTT DoCoMo. imode had no technical limitations and offered no text capacity restriction as well as full hi-res images (for the time) and cameras on almost every device. The WAP conspiracy, we learned, was essentially a conglomerate of European handset manufacturers who were so desperate to sell their backlog of hardware before companies like NTT DoCoMo exported theirs, that they’d invented WAP as a spaceholder to distract the Western market. They’d limited the development of the content market purely in the interests of their own profits. Ahh, capitalism.

By 2003 we had a strong education program offering and thanks to the international conference and festival scene were starting to be invited further afield. The British Council’s education festival took us to Thailand and Brazil, and our first trip to Australia (thanks to ANAT, the Australian Network for Art and Technology) turned into three annual visits, each offering more and more depth into what we taught and why we taught in that way. By 2005 we had run community projects with disaffected youths from the Pacific Rim in Campbelltown; Media Arts, animation and filmmaker masterclasses in Sydney; train the trainer programs and co-productions in Adelaide; and various conferences and workshops in Melbourne and Perth. Since we were so close it seemed obvious to reach out to New Zealand too, spending time with an arts organisation and University media arts partnership, colab, just entering the mobile space in Auckland.

Our early connections with the Banff New Media Institute had us returning several times to Canada as speakers, trainers and mentors. Those lead to some new relationships in USA including exhibiting with “Media Miniatures” at Pratt University and being visiting lecturers for The New School at Parsons, NYC. By 2007, while we were cheekily exhibiting our collections at the Platform International Animation Festival in Portland Oregon with a showcase and conference talk entitled “a mobile content retrospective”, the iPhone launched.

Since launching in 2001 we had managed to spend a minimum of three months of every year abroad; our knowledge of the big picture and detailed trends, similarities and differences of the international mobile scene was pretty thorough, except in China. By 2006 we had been turning our attention closer to home. We had won a tender from the Film Council UK to deliver a mobile filmmaking competition, had run a mobile documentary exchange with a youth group in Berlin, and been commissioned to produce what became “The Burgess Project”, a live literature promenade performance for the Manchester Literature Festival [you can play the trailer for the film we made about it here].

We had established an office in Manchester and had gathered our first team of volunteers. One of these wonderful people spent most of the year helping us evaluate our education program, a feasibility study, since it seemed to be the only source of sustainable income for the organisation. It was tough going. We were burned out, un/underpaid and watching the corporate sector surge on in with no regard for their makers. The London bias was getting us down and we questioned, frequently, what our original intentions had been with the company as a whole. We were makers, experimenters, and the only available income was in repeating ourselves.

We ended a year’s feasibility study with a focus group made up of generous individuals from all across the education spectrum. We explained our history; each of the programs we had delivered with community groups, schools, universities, businesses, arts organisations, individual artists and everywhere in between. We asked what, given their personal knowledge of outsourced education budgets within each of their sectors, would seem to them to be the best fit. They offered incredible feedback, sincere compliments and wise advice. We celebrated with wine and cheese and a small party. At the end of the gathering, with only myself, Ben and the small team of volunteers who had worked so closely with us for almost two years, I closed the door and turned to look at Ben, who knew what was coming. With the heaviest heart I have ever professionally held, I burst into tears and said “I’m so very grateful for everyone’s help and support over the years, but that [the vision we had all invested in building over the evening’s conversation]… that is not the company which Ben and I started, and it’s not the company that we want to run. I’m closing the-phone-book Limited.”

And that was it. I contacted everyone we had worked with around the world, saying “I’m shutting my company, does anybody want me?” and the first offer of a serious job with an actual income, something I had been lacking for a very very long time, was ANAT in Adelaide who were still running projects we had helped them to build.

The rest has become a very, very different story.

What we learned

“We don’t have WAP in our Country” – *takes handset* *opens the-phone-book.com in browser* … you not only have it in your country, you have it ON YOUR PHONE. No one knew. The corporates didn’t bother promoting it because their own sites were so lame they were ashamed of them.

“We don’t have WAP in our Country” – *takes handset* *opens the-phone-book.com in browser* … you not only have it in your country, you have it ON YOUR PHONE. No one knew. The corporates didn’t bother promoting it because their own sites were so lame they were ashamed of them.

Walled gardens were often not as walled as you might imagine – Service providers would say that only their ‘approved’ sites were accessible. Invariably you simply had to type in a url and it would work, but you never knew until you tried. Given most potential audiences didn’t know they could even try, they didn’t bother. We empowered a great deal of the future marketplace for them, completely unpaid. We even sat on conference panels with people like the co-founders of Orange while they bickered between them about who did or didn’t offer the better service when frankly what they were saying wasn’t even true. They weren’t too fond of us outing them in public, and it certainly didn’t help us get sponsorship deals, but hey.

Being an arts organisation in the UK and not residing in London makes life very, very difficult. We would send one-pagers about what we were up to over to the main cultural centres regularly, especially when travelling down for other reasons (may as well maximise the cost of those trips, as we did everywhere we went). Of course we would mostly be targeting companies/groups using buzzwords like ‘innovation’ ‘experimentation’ and ‘risk taking’ only to find that they were none of those things. We would meet London-based artists and producers overseas who would gush about our work and approach and say “how come we’ve never heard of you if you’re from UK?”. We’d just say “we don’t live in London” and they’d nod, sadly.

We were unpaid consultants more often than I care to collate – of course it’s necessary to educate people before they can see how a collaboration with you would work in a space they don’t understand. But when your time is unpaid and you’re travelling at your own expense to visit highly paid people to tell them everything you know about a sector you knew would become huge (but isn’t yet), and then they don’t bother returning your calls a week later… yeah that gets old real quick. I soon developed a spiel that told them just enough to pique their interest and give them a grounding in why this was exciting, but not so much that they didn’t need us to go further. It took a long time to build the confidence in charging for our work, too. Often people would contact us about our education programs and we’d give them our rate card. They’d say “oh, we don’t have any money…”. It’s amazing what people can find down the back of the sofa, though. Give them enough of a taste of what you can provide and some time to have a think about it and come back with an offer, and they invariably find extra funds.

We were too early (about 7years too early) and too ‘ethical’. We tried to monetise our IP by working as consultants to arts organisations, venues and businesses wanting to harness this ‘new wave’. Our ‘problem’ was that we didn’t want to make money just for ourselves, we wanted to make money for the artists we worked with too. That is still a major problem in the western world. While we were in Japan in 2002 we worked with NTT DoCoMo and learned that they shared 80% of the revenue from content sales back with their content producers; it was a business model which worked for everyone. In UK/Australia that model simply wouldn’t work because the cost of actually using the networks – the data cost of downloading a short video, for example, was so exorbitant that to add a price to that content on top would make it impossible to sell. In Japan, download data was free.

We had established as a Limited Company, more as a political statement – a nod to this potential future creative industry. We learned that the only value in establishing such limited liability is where you basically intend to go bust without destroying your own life. The extra hoops we had to jump through for this ‘political statement’ made this a total nightmare to manage. We should have stayed as a project partnership, or even just freelancers working together.

Angels – would tell us we had it all wrong. That if we would only stop paying actual writers and just get a bunch of students to give us free content then sell that to audiences, we’d be loaded. That we should work with ‘brands’ or ‘brand agencies’ to ‘value add’… i.e. get our brilliant team of creatives to basically come up with ‘fun little ad campaigns for mobile users’. Ugh.

Telcos – would tell us it was a nice idea, and even syndicated our content for a while, until they asked us to remove a story because it had the word ‘nipples’ in it. That didn’t last long.

We tried franchises of various models:

- Working with a Bulgarian arts organisation, Interspace, to establish a bespoke commission/platform for them to do what we did, only in the Bulgarian language.

- Working with the Banff New Media Institute [RIP] in Canada and their various networks to build education programs, commissions, mentoring and mLearning spinoffs.

- Had discussions with a mobile agency in China who were desperate for content for their proprietary mobile operating system, Nancy. (When we explained that our models were ethical and open and that we would never place barriers over the content we commissioned, they quickly lost interest).

- Had discussions with an agency in USA who wanted “pass-back content” that parents could hand back to their children in the car to keep them quiet. We said no.

Now

What I used to do was make spaces where other people could make and distribute (and ideally generate revenue from) content. What I do now – thanks to a successful crowdfunding campaign which went viral and bought me a bus – is attempt to use art and technology to drive social change. Making art and making change are kind of the same thing.

I used to be the phone girl, now I’m the bus girl. I’ve taken mobility to an entirely new level. I drive around Australia in my Toyota Coaster, working with grassroots communities trying to find ways that art and technology thinking and action can help drive their cause forward. I gain more than I share, it’s actually a selfish act more than you’d think. Although it hurts – stripping back one’s privilege to see what we have done and continue to do – hurts like hell.

My job has always been to make myself redundant. Once I have passed on everything I know I am no longer required and can move on to the next space/community/cause. I take all the lessons I’ve learned along the way, and maintain connections across those distributed networks for us all.

Capitalism’s job is to make itself indispensable so that you have no choice but to rely on it. And that reliance is LITERALLY killing us. It’s killing people, waterways, land, food, our health and our very identities and the self assertion of those.

IMHO redundancy, not scarcity, is the only ethical model.

I was always, always told I was wrong – not thinking like an entrepreneur enough, paying my artists too much, not living in London, that no one would engage with content on mobile devices. It took a LONG time but I now believe in my own instincts. If you are being told that you are wrong, before you believe them just sit back and contemplate who they are and what they know about your perception point. Have they seen what you see? Do they know what you know? Can they imagine the future you can imagine? If so then maybe listen to them, they might have something interesting to offer even if you disagree with them. If not, then smile and nod, maybe listen to them so you can build your lexicon of criticism and associated responses, but walk away and continue what you were always going to do anyway, because your heart and gut tells you it’s right.

We all know that the world is broken, we see and hear it all the time. Only, in fact, it’s not. The world is working PRECISELY in the manner it was designed. You, however – those of us with choice, with privilege – do not have to be broken. You do not have to accept their models as your own. This isn’t the easy path; by following your own heart you will always find yourselves moving against the flow. But if we are ever to move toward a better world that respects all human and natural life on this planet, for the few years we have remaining on it, we must all move against the flow. When you look around you and don’t like what you see, not fitting in is actually progress.

Capitalism has told us the only thing that matters is profit. Art/culture/research/pause… all deemed bad, wasteful, things because we can do nothing profitable from them (mostly). We all (I hope) know that profit is not life’s only value (it’s probably clear from all my comments that I believe it actually has no value at all, certainly not to me). But while we surgically remove all aspects of life that are not profitable, we’re disabling ourselves from all the things those elements offer.

Without art we have no mirror on, or escape from, ourselves as a society.

Without culture we have no identity.

Without research we have no curiosity.

Without pause we have no reflection, no time to let everything mulch down like a good compost and become something new, and no energy to fuel those new things.

Without anything in existence other than profit, we can only ever become robots, moving from a predetermined a to b for the pure sake of moving from a to b.

Our emotional responses are not catching up, as we can see from how normalised death, violence, hatred and bigotry have become around the globe. We cannot keep stripping away the skin without the flesh rotting.

I’m not religious, and I’m glad that religion is fading from societal norms. Not because of what religious spirituality really is, but because of the corruption over generations and generations of powermongering by the religious elite. We don’t have much spiritual thread remaining from that power infrastructure any more but that leaves us with a gaping void. There’s nothing left to inspire us, to drive us, to keep us curiously and bravely progressing. We have nothing to move forward toward.

So, what can we do to make the world a better place for everyone? Bring back respect and support for art, culture, research and pause. Respect that there are more ways to exist than just one sole craving for the least meaningful thing humankind has ever created. Reject the notion that #NoLivesMatter, and make yours count.

Selfie-flection

I said I’m not religious, but I’m going to end by preaching at you – part of the English side of my blood comes from a long line of Vicars (yeah, I know…). So here are some self-reflections I’d like you to hold on to through these last couple days of the conference, and beyond. You don’t have to answer them now and I’m putting this whole talk on my website so you can come and look at it later if you choose to. You can even come and discuss your answers with me, I’m easily found online.

- What are your personal values and how do they reflect in your work?

- Who do you need to share those values with? Who or what does your work seek to support? Why do YOU do what you do?

- What spaces or experiences do you make for others to engage within? How do you make those spaces welcoming, and safe, for all people, especially minority and threatened voices, to use – or better, adapt?

- How can you realise those goals in a society which only values profit? Or, if your only goal is profit, how can you best achieve that while not getting in the way of others whose values are more diverse?

- What can your products/services/content/experiences or lifestyle choices do to help make the world a better place for everyone? If it doesn’t or can’t, how can you rebalance that disconnect elsewhere in your life?

- And if not, if you are NOT actively seeking to help make the world a better place for everyone… how can you live with yourself?

With eternal thanks to everyone who contributed to, enjoyed and supported the-phone-book Limited in all its forms in the past and who continue to support me and my reallybigroadtrip today. If you want to economically support my (still un/underpaid!) efforts: http://pozible.com/feesable and if you want to intellectually or emotionally support them: here’s how to contact me.

Q&A

1 comment » Write a comment